This essay is the second contribution in a multi-part series of the analytical exploration of the newly launched Accelerationism Events Dataset (AED), which captures events of far-right militant accelerationism and proto-accelerationism from 1990 through November 2023. Specifically honing in on the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) seen throughout the 265 cases that comprise the AED, this essay identifies key features of accelerationist felonies committed since the late 20th century.

As elaborated in the introductory piece published earlier this year, researchers began collecting event data in July 2023 and completed final data coding in November. During these five months, approximately 300 cases were identified that featured accelerationist actors. After systematic review and exclusion of a small number of cases, the process yielded 290 initial cases. After additional phases of inclusion consideration, a final dataset of 265 cases was identified. The dataset includes 20 cases occurring during the Summer 2020 wave of racial justice protests and 79 cases occurring during the 2021 attack on the US Capitol.

For the purposes of this report, the TTPs assessed in each case include the intended target (the who or what), the physical target (the where), and the ideological target (the why), as well as the criminal method(s) affiliated with each felony.

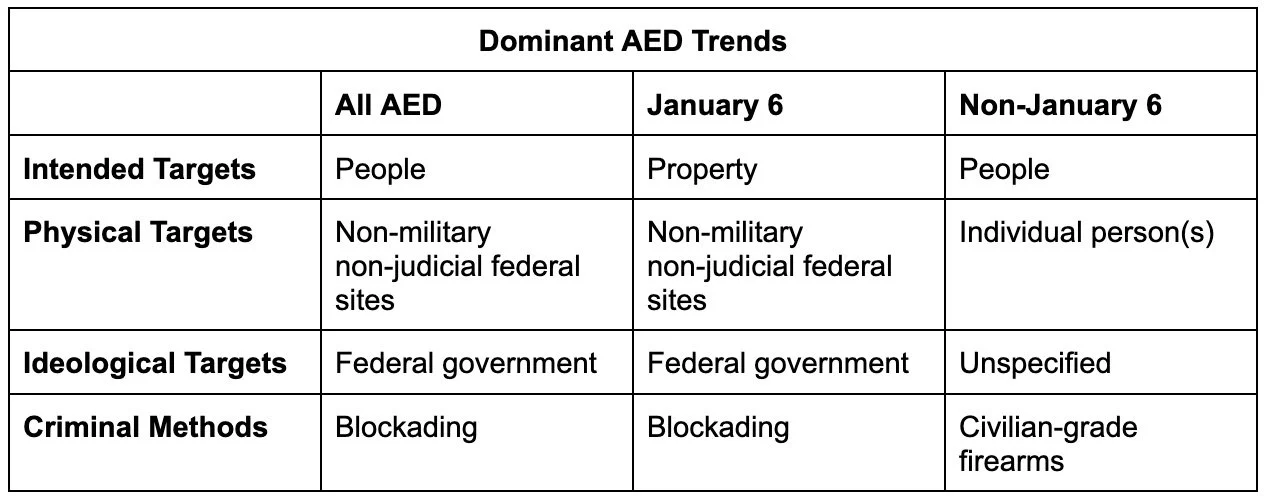

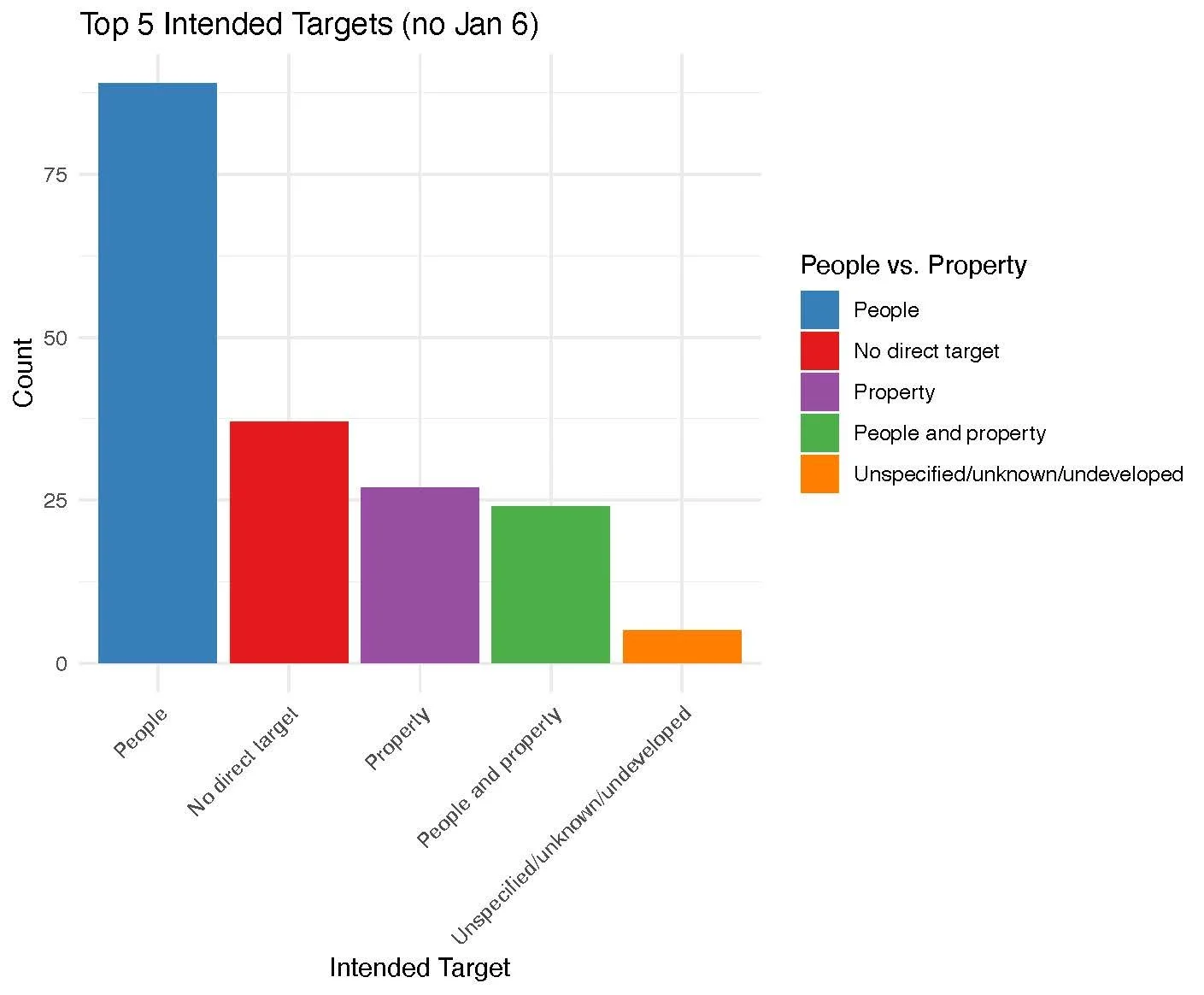

To determine the dominant intended targets of accelerationist cases, we divided the AED data into five categories: No direct target (e.g., bank robbery, providing material support), People, People and property, Property, and Unspecified/unknown/undeveloped. Given accelerationists’ fundamental focus on grievances related to anti-government sentiment, it was important to consider both individuals targeted (such as law enforcement officers or public officials), as well as property (such as federal judicial buildings). Additionally, we conducted a deep-dive into the specific physical targets involved in the AED cases (e.g., whether or not the property was public or private, or state, federal, or municipal, etc.).

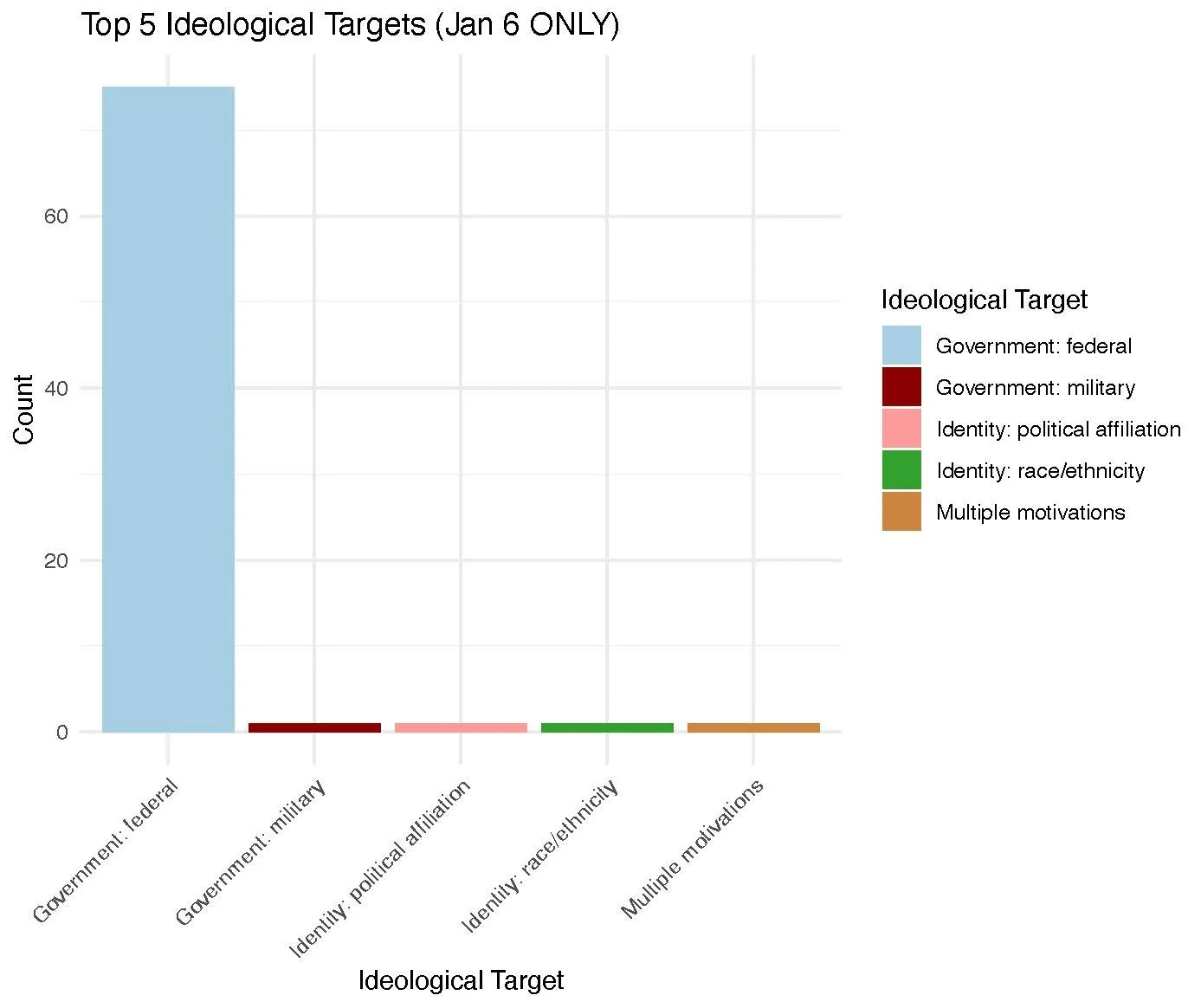

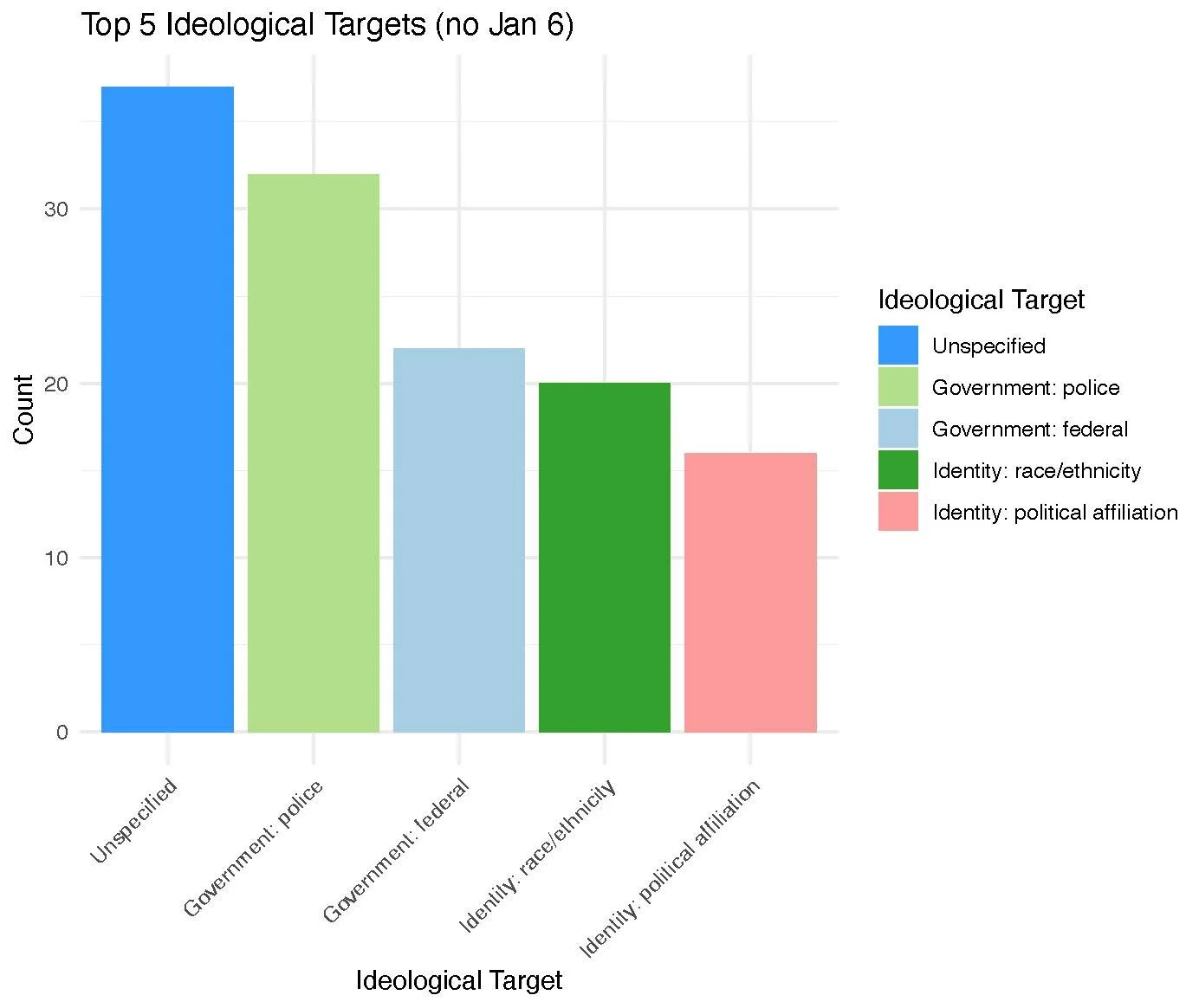

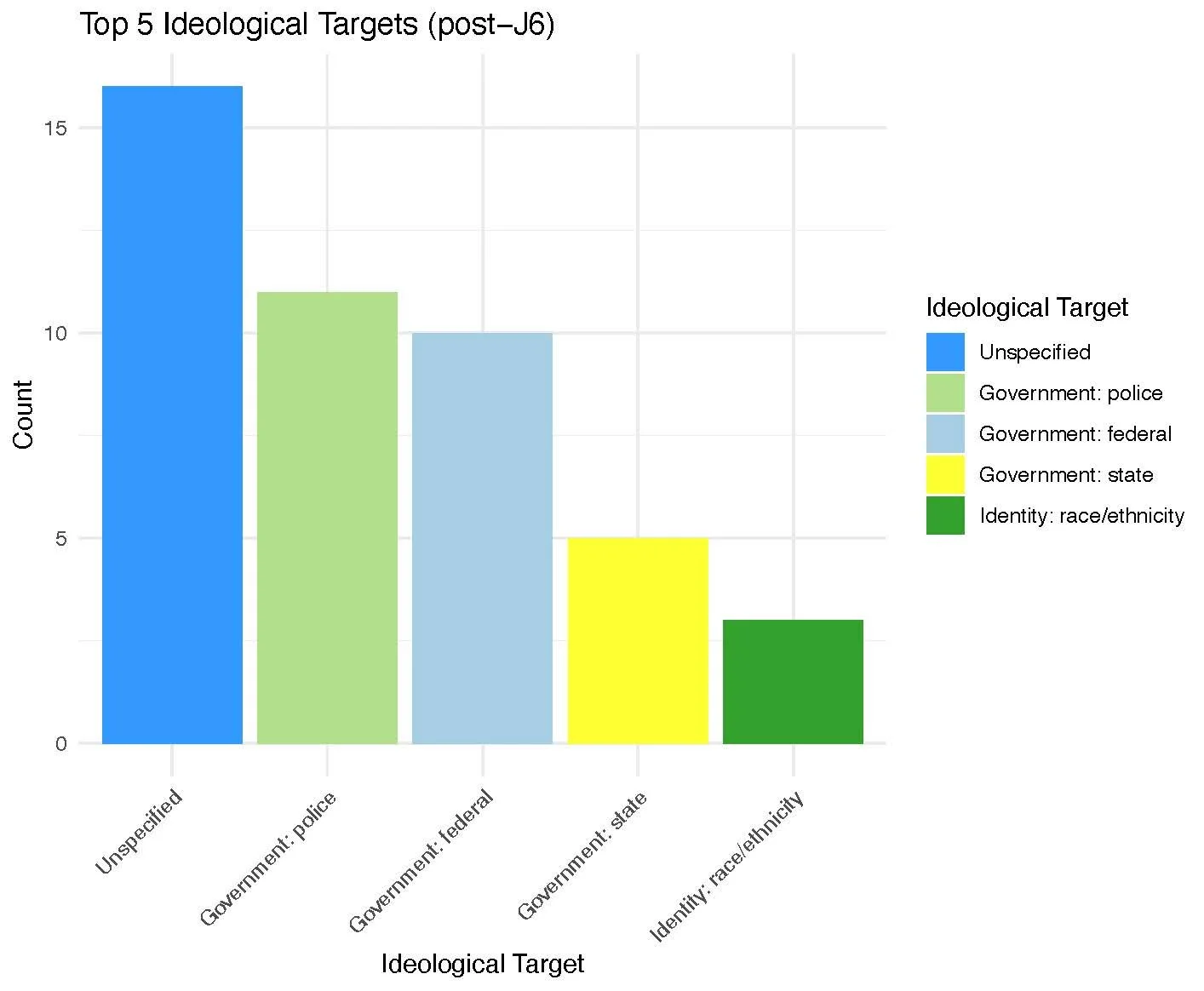

It was important for our team to identify the primary ideological targets involved in AED cases ––the characteristics of the target that motivated the defendant to commit the specific crime –– whether the target was affiliated (or presumed to have a connection) with the US government, connected to a particular identity-based community (e.g., race/ethnicity, nationality, sexuality/gender, political affiliation), or was affiliated with multiple or unknown characteristics that were key motivating factors for the defendant.

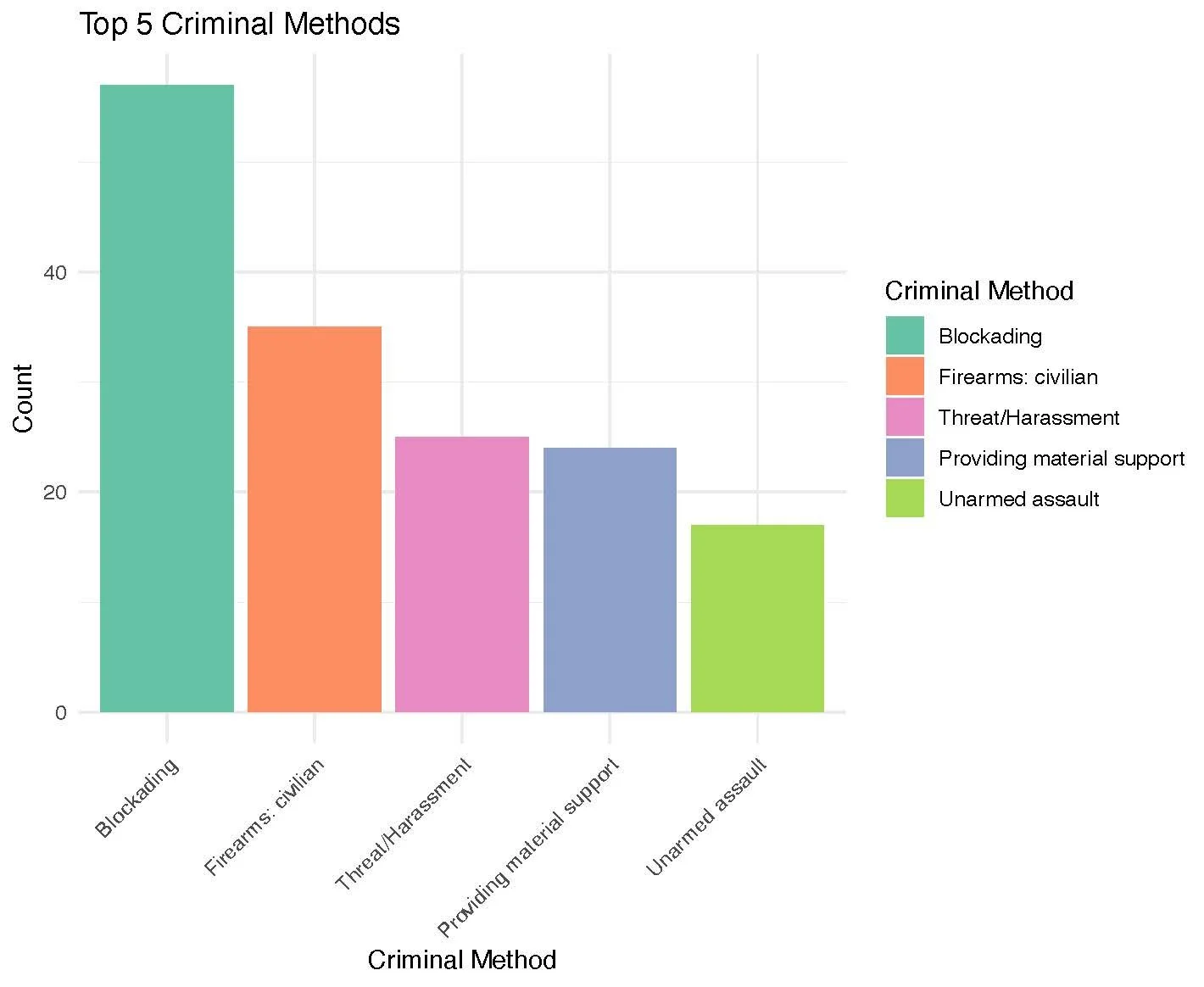

Lastly, we documented the criminal methods, or the means through which AED defendants carried out their crime(s), of the AED. Five dominant tactics were present across the dataset:

To learn more about the specific variables of each aforementioned category, check out the Prosecution Project’s codebook here.

Given the aforementioned definitions, this piece seeks to identify the primary targets in these cases and their affiliated criminal methods. The data below highlights high-level trends for all AED cases and also data visualizations that break apart:

Lastly, it is important to note that while over 90% of the cases identified in AED occurred between 2016 and 2023, 9% (24 cases) occurred prior to 2015, which, as defined in the introduction to this series, was a period wherein these “neo-fascist, proto-accelerationist groups adopted many of the tactics, techniques, and rhetorics seen in contemporary accelerationism, though they emerged prior to the framework’s identification and naming.”

The overarching AED data (Figure 1) illustrates that the primary intended targets for all AED cases (including January 6) are People, followed closely by Property, People and property, and No direct target, respectively. This trend is reflected in recent accelerationist crimes and scholars’ understanding of these actors, as these anti-democratic actors seek to exacerbate institutional vulnerabilities, primarily through the targeting of officials and buildings.

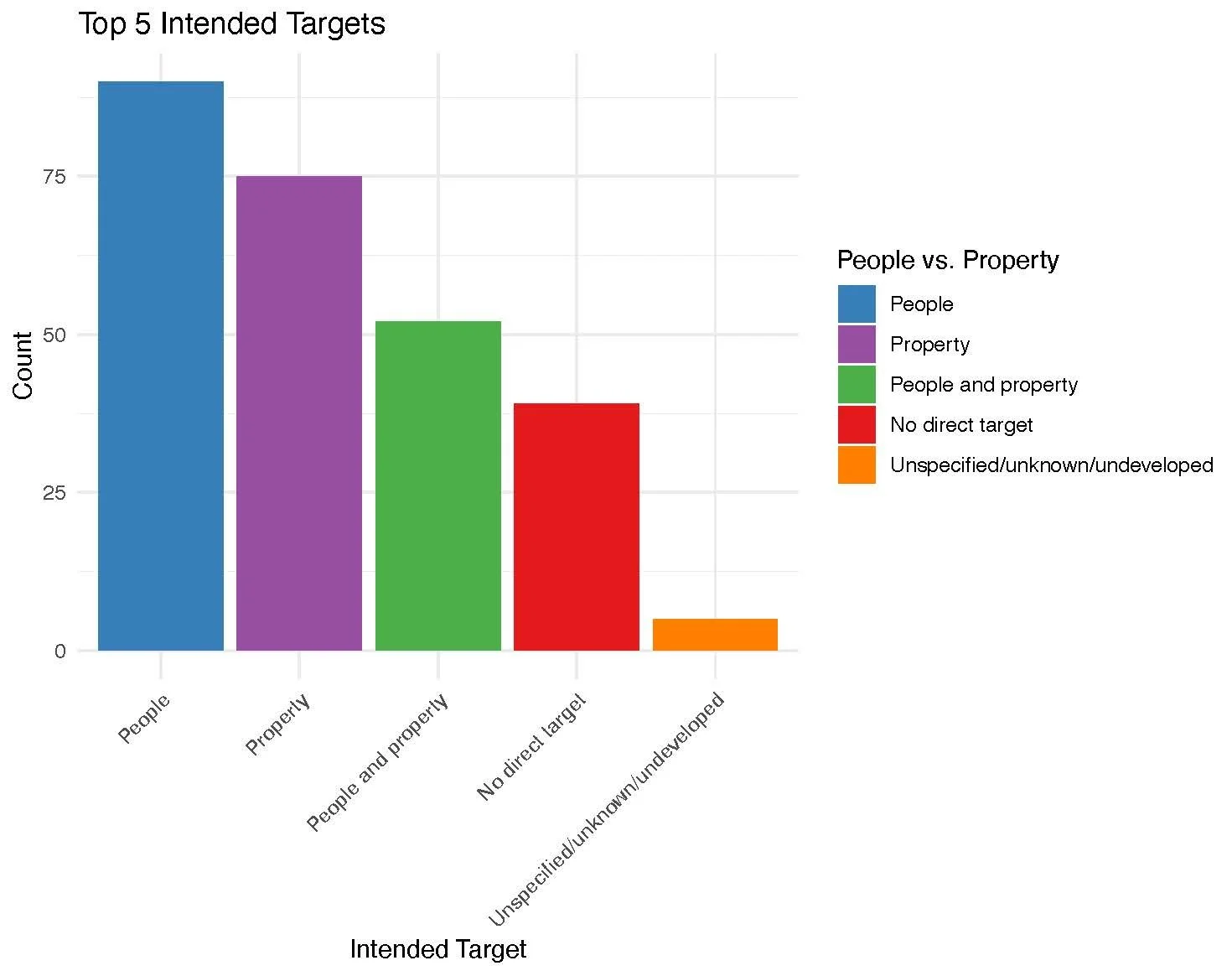

When only considering primary targets involved on January 6, 2021, at the US Capitol (Figure 2), Property was the clear dominating intended target, followed by People and Property, with very few cases involving People or No direct target. This should not come as much of a surprise, given the key motivations involved on January 6, where insurrectionists’ core goal was to take hold of the US Capitol and fend off any law enforcement personnel or public officials on that day.

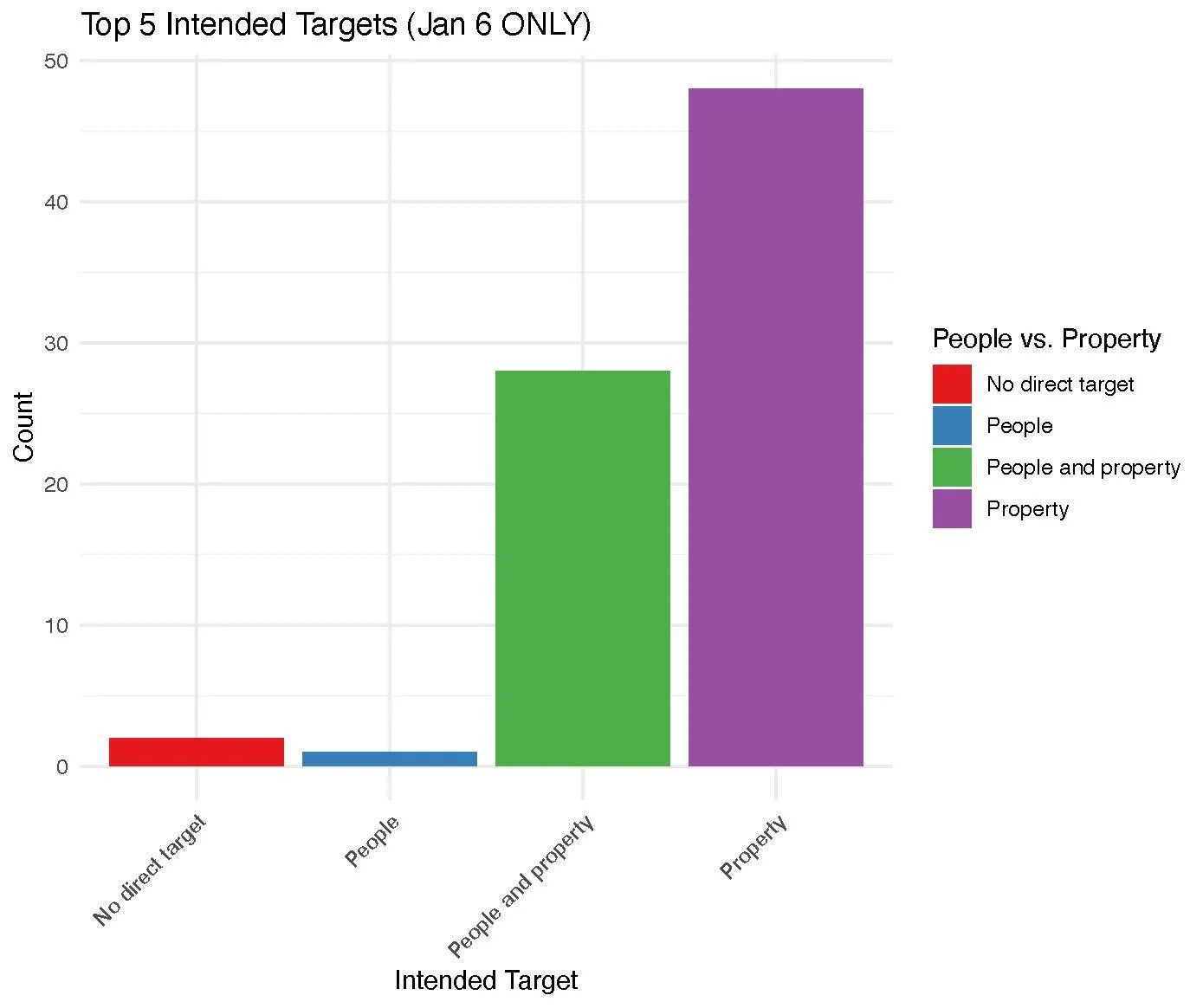

When removing January 6 defendants from the data (Figure 3), People are the dominant intended target, which is a complementary trend of the overarching AED data in Figure 1. However, unlike the other two data visuals above, non-January 6 cases have more indirectly intended targets than Property and People and Property, respectively.

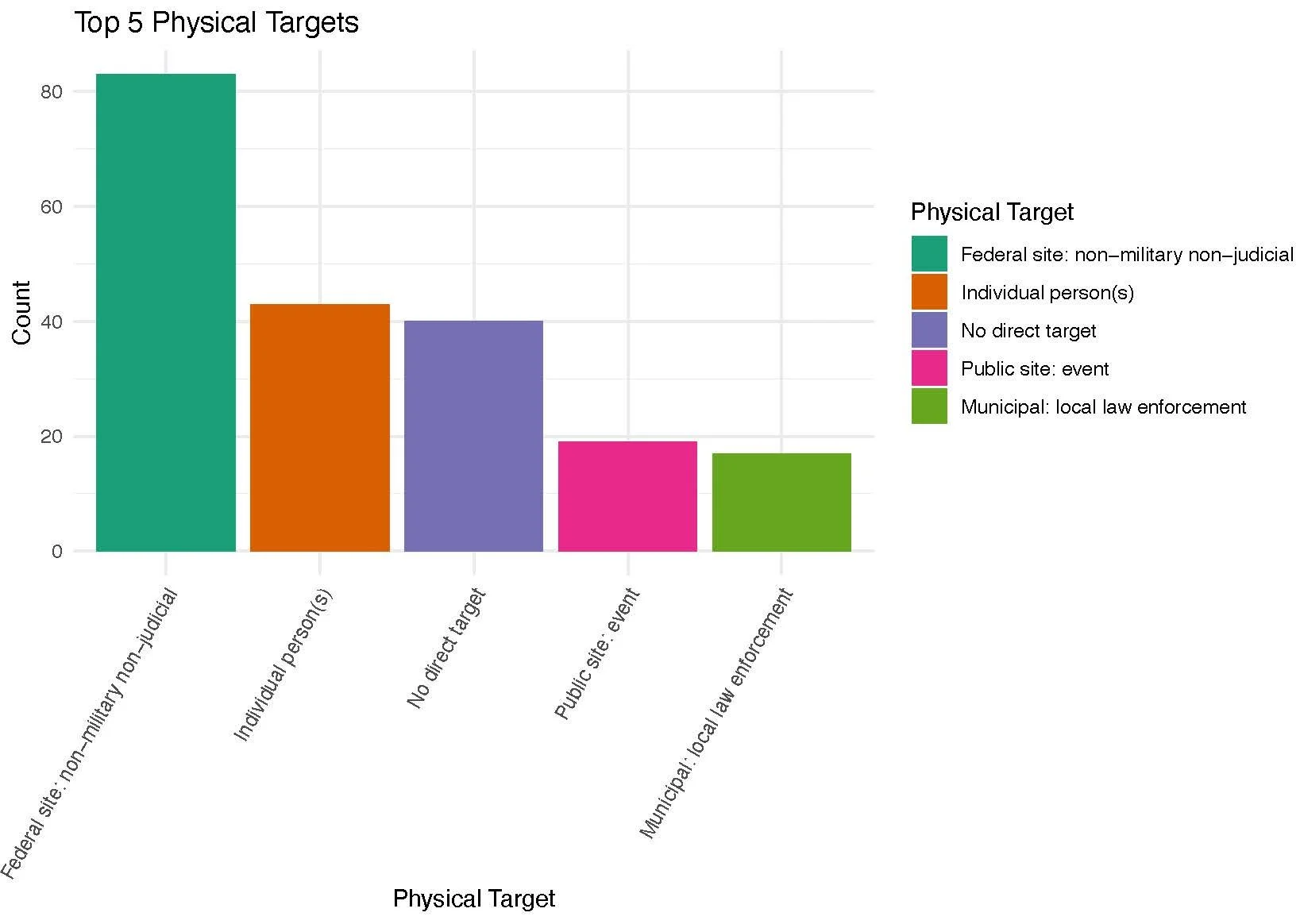

As seen in Figure 4 below, non-military and non-judicial federal sites, such as the White House and US Capitol, are the clear primary physical targets for all actors captured from 1990 to January 2024 in the AED. This trend should not be surprising, given the representation of January 6th actors in Figure 4.

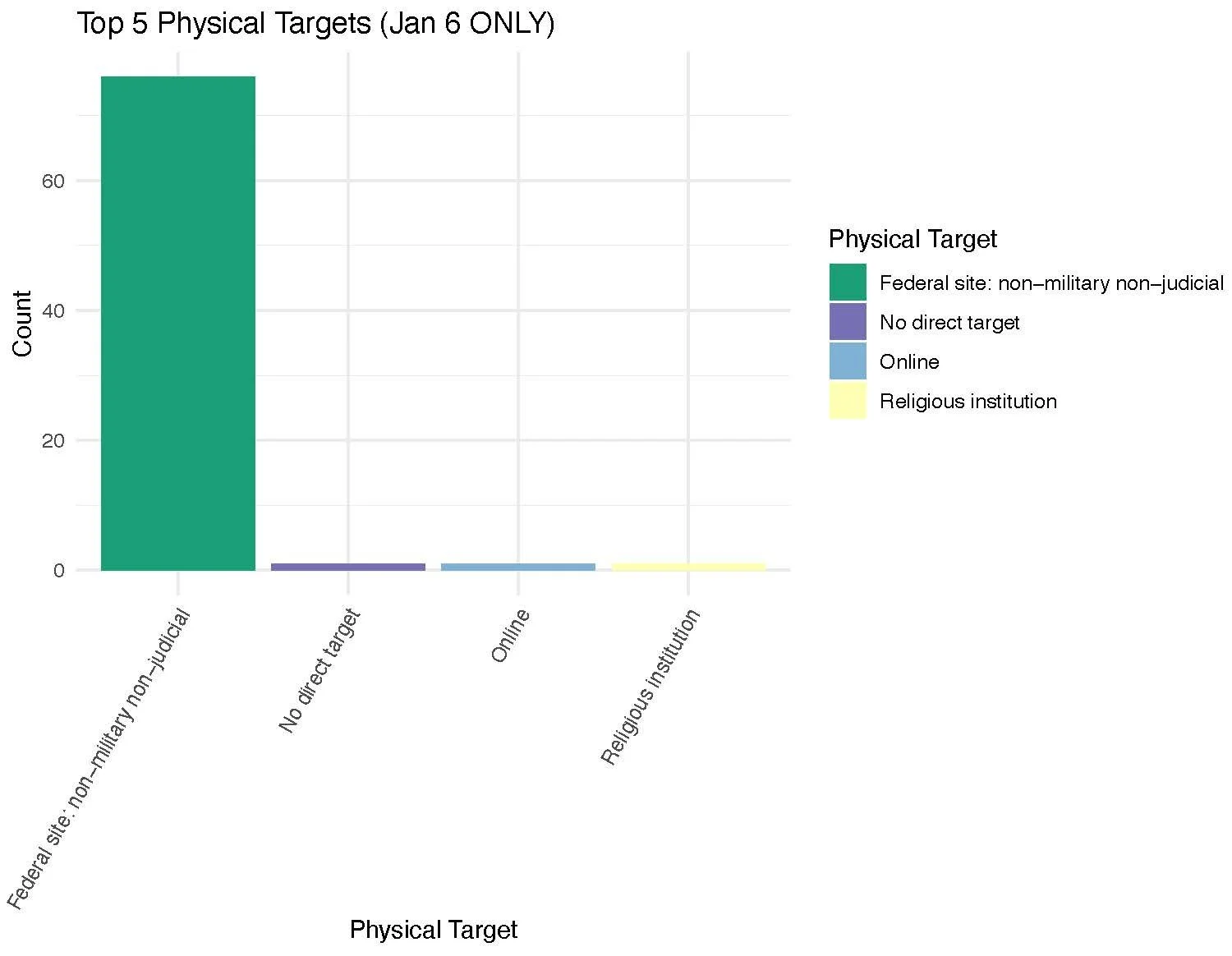

When taking a closer look at January 6, specifically (Figure 5), it is clear that data from January 6 cases skew the overarching AED data above in Figure 4.

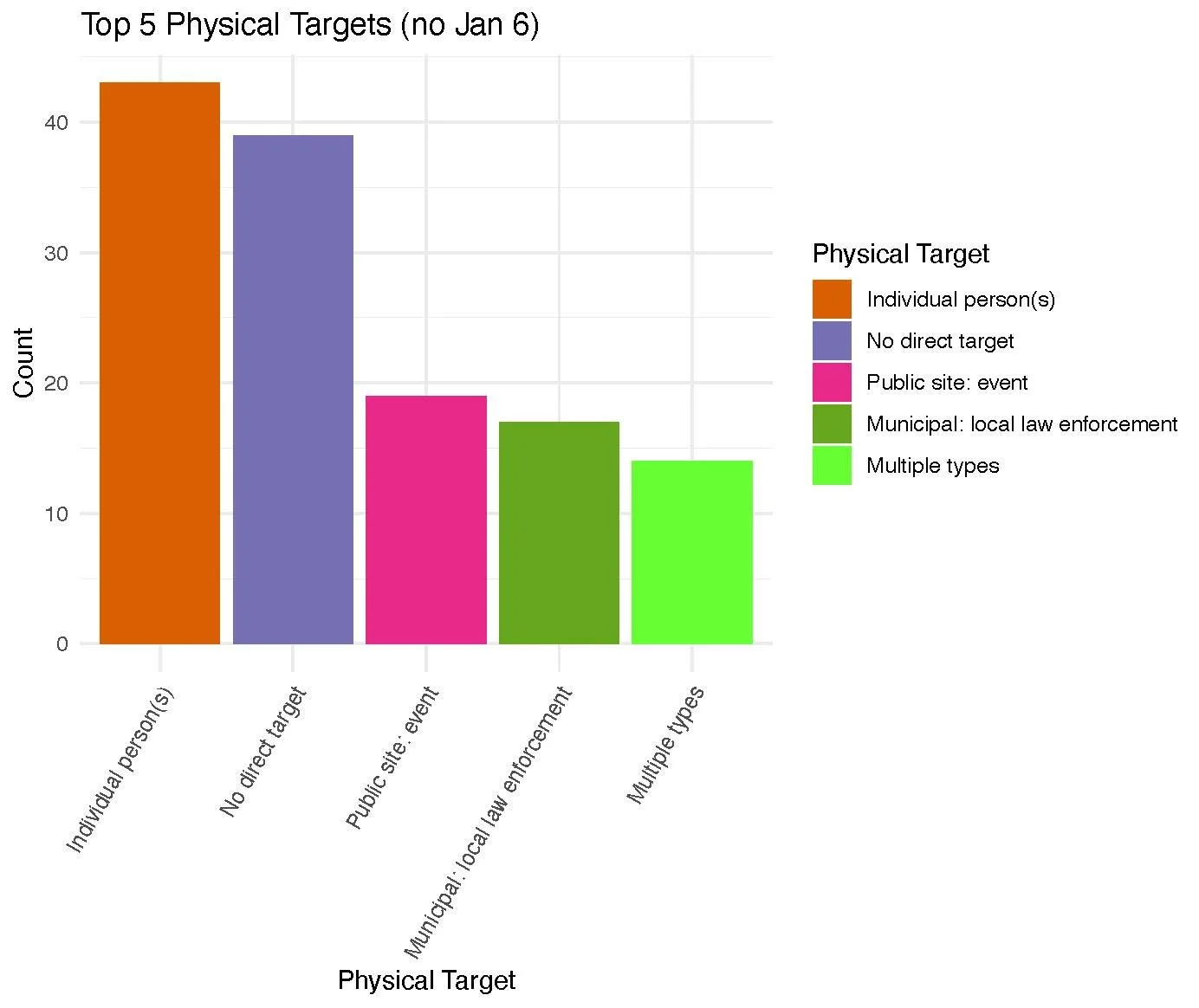

Figure 6 illustrates that when excluding January 6 defendants and their felonies, Individual person(s) are the primary physical target for all other crimes in the AED database. Further, the only physical target that Figures 5 and 6 share is No direct target, making it clear that physical targets involved on January 6, 2021 by these actors are outliers when compared to the rest of the AED.

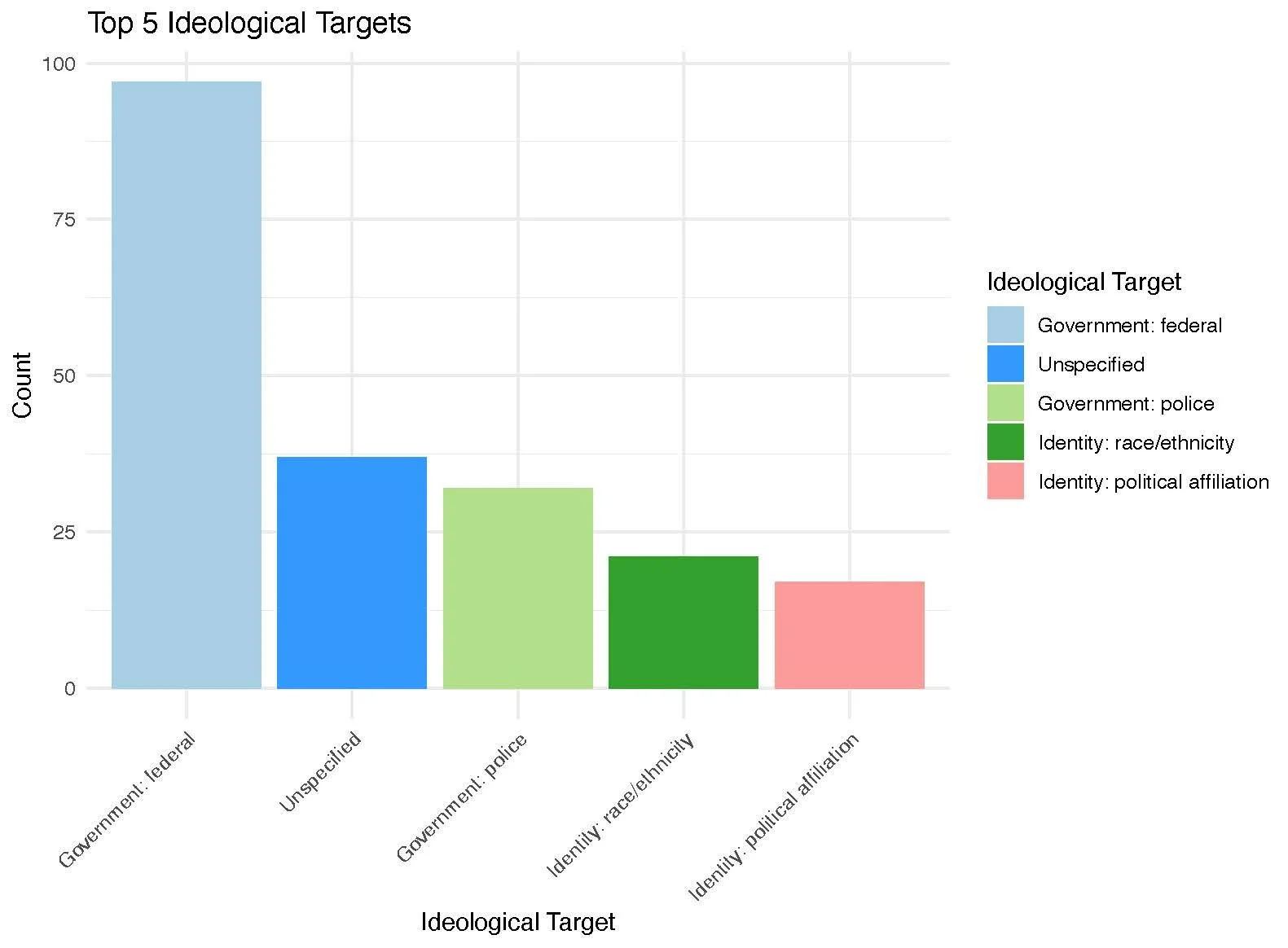

AED defendants’ ideological targets across the three compartmentalizations of AED data share three primary targets: Government: federal, Identity: race/ethnicity, and Identity: political affiliation. However, the leading outlier for all AED cases (Figure 7) seems to be skewed by cases from January 6, 2021, given that the events of January 6 (Figure 8) were clearly motivated by grievances against the federal government.

When removing January 6 cases from the data, grievances against the federal government are only the third most dominant ideological target, preceded by Unspecified and Government: police grievances, respectively.

In an effort to better understand the “why” of these cases, we also considered ideological targets of all non-January 6 felonies in the time period following the January 6 insurrection, in order to identify whether defendants and their affiliated crimes appeared to have been motivated or deterred by the insurrection. As shown in Figure 10 below, the three most dominant ideological targets have not changed, however, crimes motivated by state governments seem to have increased and grievances involving race and ethnicity are still present post-January 6.

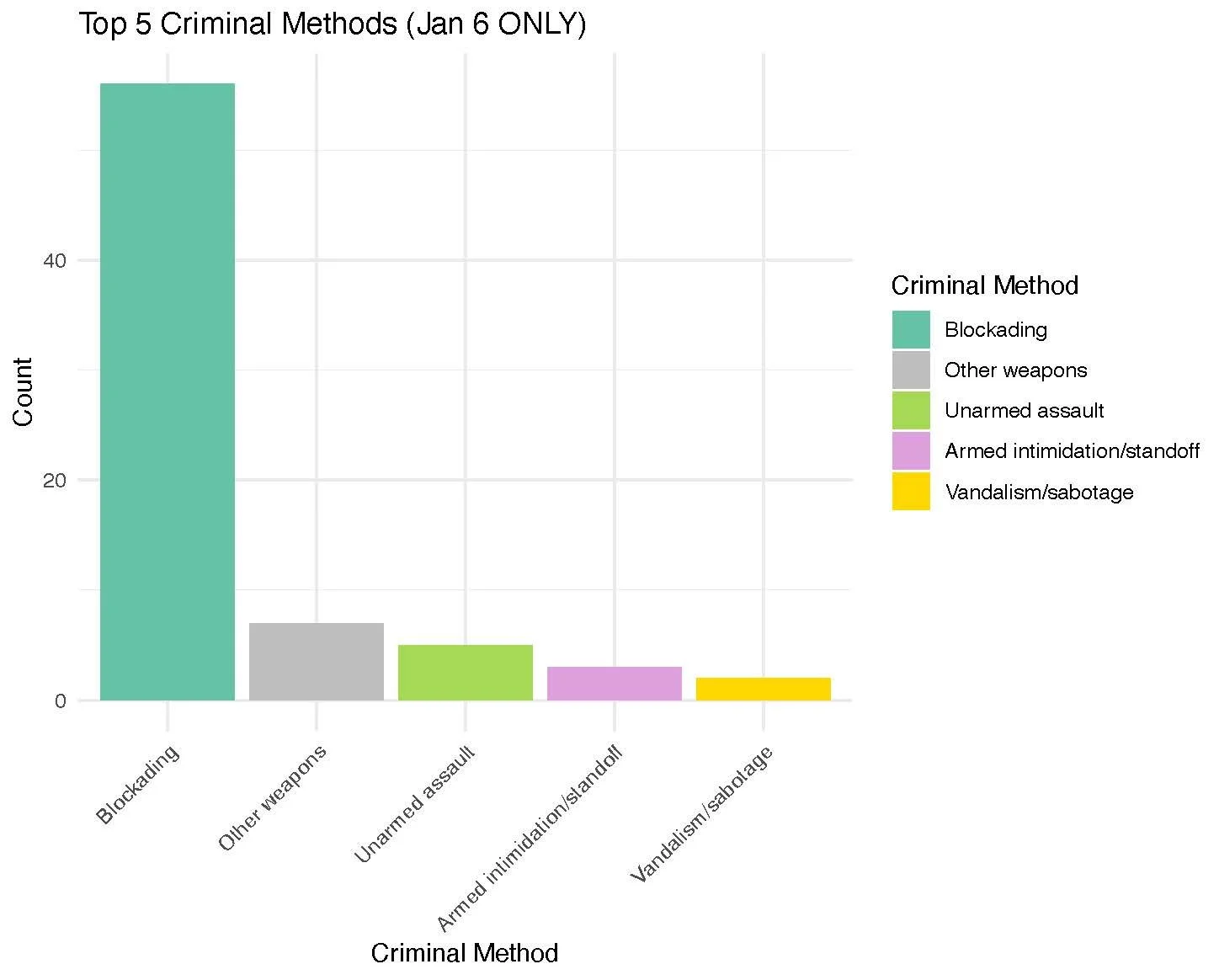

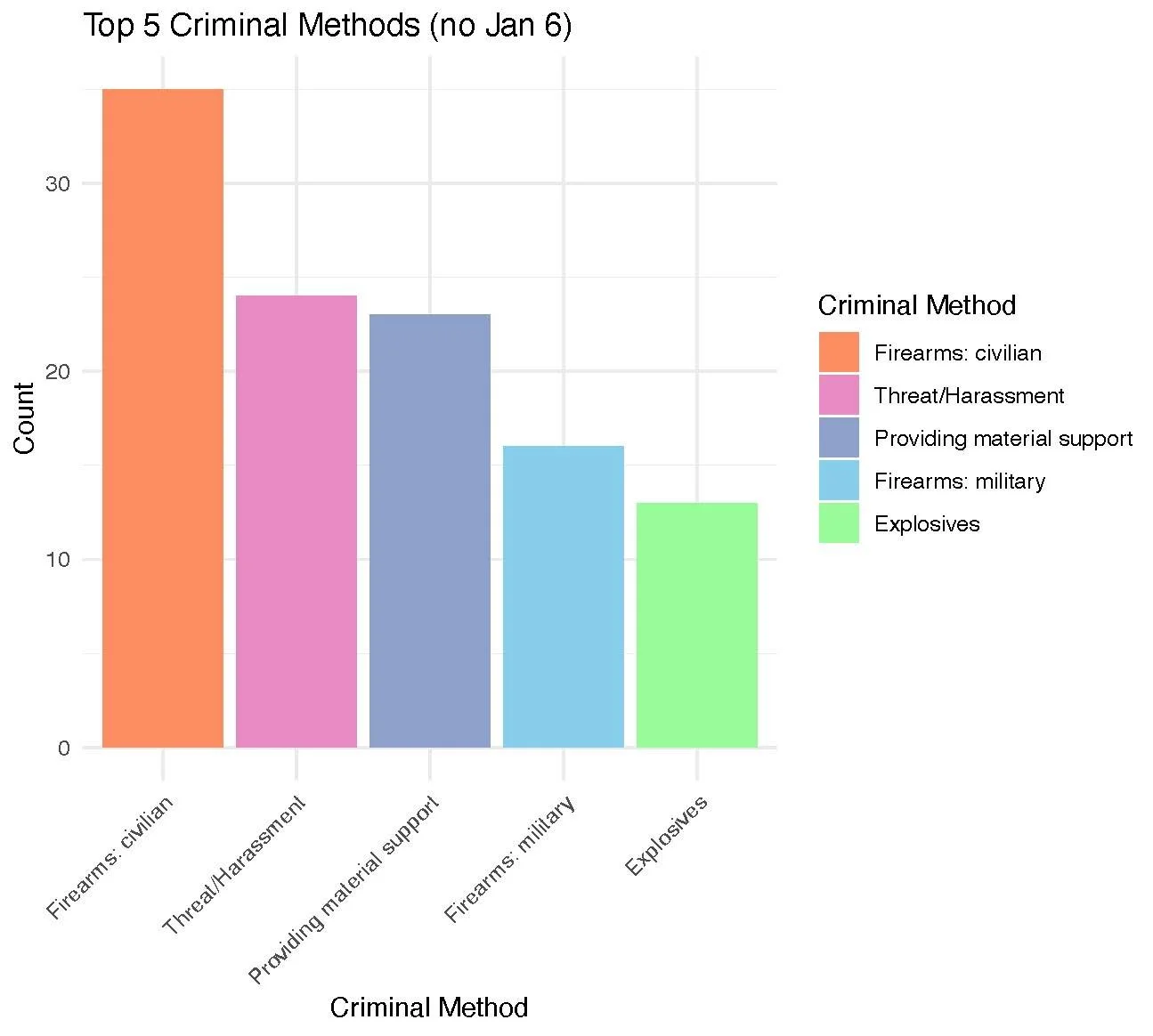

As shown below, Blockading was the dominant criminal method for not only AED as a whole (Figure 11), but also for January 6-specific cases (Figure 12). However, blockading appears to have been the only significant skewing variable between January 6 cases and the rest of the felonies included in the dataset. The second-most dominant criminal method in Figure 11 is civilian firearms (which are not included in January 6-specific cases).

Another important differentiation between January 6-specific data and non-January 6 data is the use of firearms and other weaponry present in non-January 6 cases (Figure 13), compared to primarily unarmed criminal methods during the insurrection at the US Capitol (Figure 12), aside from when firearms were used as intimidation tactics, likely due to Washington, DC’s gun laws being “some of the strongest gun laws in the country.”

Ultimately, while January 6, 2021, was a historic outlier for many reasons, there were consistent trends across all accelerationist cases, namely:

This is the first piece exploring the data patterns of the AED. The next publication to follow will focus on the demographic patterns, and will be later supported by publications that will dive into the temporal and geographic trends of criminal defendants, defendants’ group affiliation and ideological orientations, and the legal outcomes and processes of criminal cases.

Mary Bennett Doty is a Senior Research Specialist at Princeton University’s Bridging Divides Initiative, as well as a Senior Coder with the Prosecution Project. Mary Bennett’s research focuses on the monitoring and mitigation of offline manifestations of political violence. The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the views of her employer.

This report is part of a multi-publication series led by Dr. Michael Loadenthal, and supported by research conducted by Samantha Fagone, Grace Stewart, Olivia Thomas, and Bella Tuffias-Mora.

To check out the introduction to this series, read Dr. Loadenthal’s piece here.